— Originally published by Fox News on January 27, 2020, original link: https://www.foxnews.com/us/holocaust-survivor-jerry-wartski-auschwitz-liberation —

In the nearly 75 years since the end of World War II, Jerry Wartski never uttered a word about what he endured after the Nazis invaded his native Poland.

Those around him knew him as a Holocaust survivor who survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, but the Manhattan businessman never offered any details.

He never spoke of losing his parents and his home to hate.

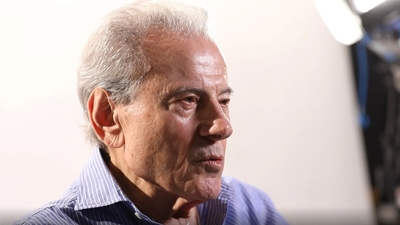

“I saw a lot of people were able to talk about it. I just couldn’t,” Wartski, 89, told Fox News in his first sit-down interview with the media, just ahead of the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liberation today. “My kids, they learned everything in school. They didn’t learn from me. … They didn’t even ask me a single question about it.”

Wartski was born to Jewish parents in Osjakow, Poland, on May 18, 1930. He was 9 when the Nazis invaded Poland – triggering the start of World War II.

“The news was already traveling from Germany. We knew that for the Jews it was not that good,” the soft-spoken survivor recalled. “It started right away. They put out the martial law, and we were told that Jews could not go to public school. …

“We were told Jews had to put armbands on and told that we weren’t allowed to walk on the streets. We had to walk in the gutters, not on the streets,” he continued, struggling to keep his voice steady. “Then they changed it to the Star of David that you had to wear.

“And that’s how it started.”

Several months into the war, the Third Reich began setting up ghettos in cities and towns across their occupied lands with the intention of segregating Jews and other “unfavorables” from the rest of the population. These anti-Jewish measures culminated in the policy of extermination the Nazis called “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

Wartski and his family – his mother, father and brother – were sent to the ghetto in Osjakow in 1941. The mass deportations soon began.

“When the selection started, they looked left and right, old and young,” Wartski remembered. “The ones they took away, they put them in trucks, and outside of town (in Chelmno), they gassed them and then they dumped the bodies. So we lost all the children and all the elderly people all in one day.”

After the deportees were put on trucks, the SS – or Schutzstaffel, Adolf Hitler’s brutal paramilitary force – returned to round up any remaining young children. Wartski, who was 11, said he and two other boys found some bricks to stand on to make themselves look taller. It seemed to work momentarily, but they were caught and sent to the ghetto’s front gate.

“But I was lucky because the last truck (had) already left. So I didn’t go,” he said. “That saved me. My first lucky star during the war.”

In summer 1942, the Nazis liquidated the ghetto, sending able-bodied Jews to another ghetto in Lodz and the rest to the Chelmno extermination camp, which had served as a pilot project for the Holocaust.

“They called it Litzmannstadt (the Lodz ghetto). And in Litzmannstadt, we saw that people had it much worse than we did,” Wartski recalled.

In Lodz, he and his family did what they could to avoid being selected for deportation by the SS. By early 1944, the Nazis began liquidating the ghetto – with the initial wave of Jews sent to Chelmno.

The rest went to Auschwitz-Birkenau, with its vast expanse of crude barracks and the Nazi-built crematoria, where 1.1 million people were fatally gassed and incinerated.

Wartski and his family were put one of the last transports out of Lodz, bound for Auschwitz.

“In Auschwitz, it was the same selections are before,” he recalled sadly. “That’s where I lost my mother. They gassed her in Auschwitz.”

He and his father and brother were only in the camp a few weeks when they were taken to a nearby forced labor camp.

In fall 1944, as the Soviet Red Army was making its way west through German-occupied Poland, Heinrich Himmler, the main architect of the Holocaust, ordered the SS hide evidence of the mass murders at Auschwitz by destroying the gas chambers and crematoria.

By mid-January 1945, thousands of Auschwitz detainees were evacuated on foot in death marches. The fewer than 9,000 who remained in the camp were deemed too sick to move.

“We went on a big march that took a long while and we lost a lot, a lot of people,” Wartski said. “They then put us in a cattle train – you couldn’t even move when we started. A week later, you could sleep on the floor because there weren’t many people left.”

The train stopped in Nordhausen, a sub-camp of the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp. The camp was considered an extermination camp for ill prisoners, who died due to starvation or lack of medical care.

“My father passed away of starvation less than a month before we were bombed out,” Wartski said.

On April 3, 1945, Nordhausen was bombed by the U.S. Air Force, who thought it was a German munitions depot. The bombing killed many of the prisoners, but days later, the camp was liberated.

“I was still 14 years old,” Wartski said

After the war, he and his brother – after returning to Poland briefly – went to a displaced person camp in Germany, where they awaited permits to come to the United States.

On July 29, 1949, aboard the USS Gen. C.H. Muir, the brothers arrived at Ellis Island in New York Harbor.

“I was in a different world. Everything was different. You couldn’t compare,” Wartski marveled. “We came over here, and you saw the sugar on the table in the restaurant. You just couldn’t believe it.”

As the years rolled by, Wartski, now a successful real estate investor in Manhattan, said he just couldn’t bring himself to share his story. It was just too painful to relieve.

However, a trip back to the hallowed graveyard where his mother perished five years ago, inspired him to open up.

“Now I see that there are not a lot of people left who can tell the story,” he said. “The stories that you hear are just unreal and unbelievable, and you have to talk.”

Wartski is in Poland today to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the camp’s liberation. He is joined by his wife and two sons and a group of friends.

Leave a Reply